Cydonia oblonga

In the past, a quince tree or two used to appear in pretty much every home orchard, but finding one today is quite rare.

Last time I was in the specialty grocery store near my house, I heard some shoppers marveling and musing about the “weird” basket of fruits sitting next to the apples.

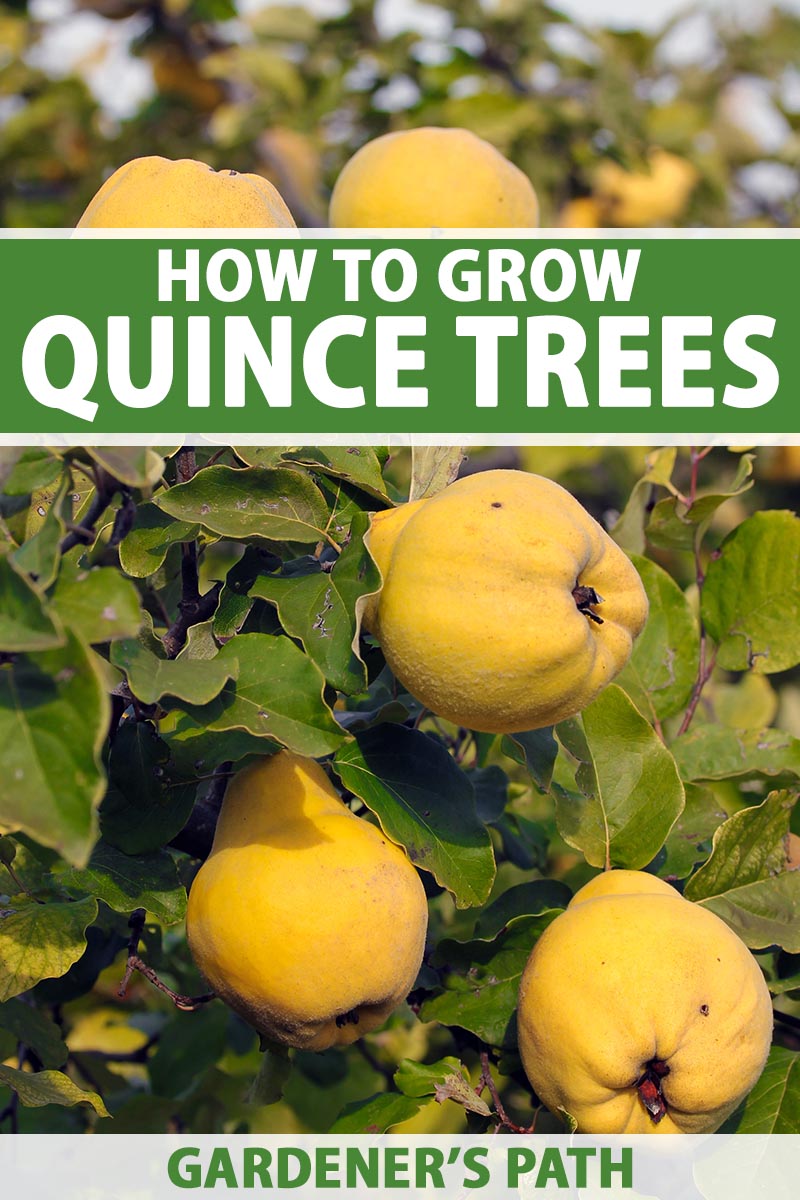

In fact, they’re the least popular fruit trees in the US. I can’t totally blame gardeners for forgetting about them. Quince fruit doesn’t look like much.

The shape is like a cross between a hard, knobby apple and a pear, with cellulite-like dimpled skin. Mostly they can’t be eaten raw off the tree unless you develop a taste for them. They aren’t “easy” like apples or pears.

But the fragrance will knock your socks off. It’s a combination of floral, fruity, and sweet with a complex hint of spice. It’s like mango, guava, pear, rose, and violet wrapped up together.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I’ve bought quinces at the store that didn’t have the signature aroma, though they cooked up just fine.

I begged and pleaded with the fruits to erupt in fragrance, but they never did. The ones straight off the tree? They’re reliably magnificent. That’s why you should be growing your own.

While the fruits are incredible and are worthy of a comeback, the trees are pretty spectacular, too. One of the most interesting bonsai I’ve ever seen was a Cydonia. The trees take on a gnarled, twisted shape as they age.

In USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 9, quince trees make a beautiful and fragrant addition to the garden. Let’s get to know these plants by discussing the following:

Before we get into the cultivation details, let’s make sure we’re all on the same page. There are two plants that go by the same common name and we don’t want to confuse them.

What Is Fruiting Quince?

Fruiting or true quince (Cydonia oblonga) is a member of the Rosaceae family, closely related to apples and pears, and is the only species in the Cydonia genus.

It’s often confused with flowering quince (Chaenomeles spp.) because they share a common name, but those winter-flowering shrubs aren’t the same, though the plants are closely related.

True quince trees are medium-sized and typically stay below 25 feet tall and 20 feet wide, though wild specimens are about half that size, and grafted dwarf options are available. They naturally have a shrubby growth habit, but gardeners often cultivate them as trees.

On the species type, the leaves are ovate and can grow up to four inches long. The blossoms are heavily fragrant, white, and have five petals, like all plants in the Rosaceae family. Cultivars may have larger leaves and flowers.

Quince fruit is categorized as either apple- or pear-shaped, which simply refers to the shape of the fruit. It either has the rounded shape of an apple or the elongated, thin-necked pear shape.

When young, quince fruits are green and have a bit of fine hair covering the skin. By the time they mature, they will become bright yellow and hairless.

The fruit is high in pectin, which makes it ideal for jellies and jams, but along with its naturally firm texture and astringency, also means that it tastes better when cooked rather than eaten fresh.

The aromatic magic comes from ionones and lactones, compounds that give quince fruit its yellow hue.

Plants in the Rosaceae family are known to hybridize naturally within genera, and there are pear-quince and apple-quince hybrids out there.

Pyronia veitchii is one such natural hybrid between a pear and a quince and is cultivated commercially.

Cultivation and History

Quince originated in the Caucasus region of western Asia and has been cultivated in the Mediterranean for centuries, even appearing in Roman and Greek legends.

The heady fragrance from the fruits and flowers has also been harnessed as a perfume known as melinum and was used in Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Pliny the Elder wrote that the perfume was “used as an ingredient in unguents, mixed with omphacium, oil of cyprus, oil of sesamum, balsamum, sweet-rush, cassia, and abrotanum” in his Natural History of Exotic Trees, and An Account of Unguents.

Quince has since made its way around the globe. It became wildly popular in France, Spain, and Portugal, along with the United Kingdom during the Middle Ages.

In France, they used quince as rootstock for growing pears as far back as the 1500s, and a preserve made out of the fruits, known as contignac, was gifted by and to wealthy families.

The original marmalade was made out of quince fruits, not oranges.

Settlers brought the fruits to the New World in both New England and Mexico because they contain a lot of natural pectin, which means you can readily create jam and jelly.

Throughout the 1800s, you could find a quince tree growing in most homesteads, and some even escaped into the wild, though they aren’t invasive.

But as time went by, people preferred the fresh-eating apples and pears to a fruit that requires processing. Plus, Charles Knox introduced powdered pectin in the 1890s, rendering fruits that contain lots of pectin unnecessary.

Around the same time, pure cane sugar biased the human palate toward sweeter foods, so the more bitter and sour fruits and vegetables went out of style.

By 1922, it was “neglected” and “least esteemed” of fruits, according to botanist Ulysses Prentiss Hedrick.

As of 2009, there were just 250 acres of quince in cultivation in the US, with about 106,000 acres worldwide. For comparison, there are about 322,000 acres of commercially grown apples in the United States alone as of 2021.

More commonly, quince trees are cultivated for use as dwarfing rootstock for pears.

Quince Tree Propagation

Don’t try to grow quince from seed. It’s possible, but it’s not recommended.

Stick to propagation via stem cuttings, grafting, layering, or just buy a tree from a plant nursery to get started.

From Cuttings

Quince grows well from both hardwood and softwood cuttings.

This project should be started in the spring, taking hardwood cuttings in early spring and softwood cuttings in late spring. Only take stem cuttings from a quince tree that is healthy.

Softwood is green and pliable; hardwood is firm and grayish-brown.

Select a healthy stem and remove a six- to eight-inch cutting, making the cut at a 45-degree angle with a clean, sharp pair of clippers.

Place the cutting in a cup or bucket of water so the cut end stays moist. I recommend taking at least six cuttings because the chances are pretty good that at least one of them won’t make it, so you’ll want spares.

Remove all but the top two or three leaves, if present. Softwood cuttings will typically have leaves, where hardwood will likely not.

Fill large plastic cups or four- to six-inch growing containers with potting soil. Dip the cut end in rooting hormone and insert it into the soil two inches deep. Firm the soil up around the cutting and moisten the medium.

Place a plastic bag over the cutting, propping it up with a chopstick or something if necessary, to keep it from touching the cutting.

Place the cutting in a warm area that stays between 65 and 75°F in bright, indirect light. Keep the soil moist but not soggy.

Now it’s time to play the waiting game. Softwood cuttings typically take root within three or four weeks. Hardwood cuttings can take months to form roots.

To check whether your quince cutting has rooted, you can gently pull on the stem to see if it resists. If it does, it’s likely formed roots, though the best way to be sure is to push your hands gently under the plant and lift it up to have a look.

Once roots have formed, remove the cover and move the cutting into a sunny spot indoors. Leave the cutting in the pot until the fall, when you can harden it off and place it in the ground.

Hardening off is the process of gradually introducing the plant to the outdoor conditions. Do this by setting the plant outdoors for an hour and then bringing it back inside. Add an hour each day for a week.

From Grafted Rootstock

For a time, horticulturalists used to graft quince onto pear rootstock, but the resulting trees weren’t reliable. These days, grafting onto quince rootstock is the standard.

Grafting is a more advanced process of propagation that requires both a scion, which is the top part, and a rootstock, which is the bottom part.

You can purchase both parts or grow them yourself. Most gardeners purchase the rootstock and then use a scion from an available plant.

Take the scion in the late winter from a healthy quince plant. Look for a soft, pliable branch and cut a six- to eight-inch length of stem at a 45-degree angle.

Wrap the end of the scion in a moist paper towel, place it in a plastic bag, and set it in the refrigerator until mid spring. At that point, plant your rootstock if it isn’t already in the ground.

To make precise cuts on both the scion and the rootstock, you’re going to need a grafting knife. These are fairly affordable and will make all the difference when preparing your graft union.

Double Blade Grafting Knife

You can find a double blade grafting knife and some grafting tape at Amazon.

On your rootstock, cut a line down the center of the stem using a grafting knife. If necessary, tap it into the wood using a rubber mallet. The slice should be about two inches deep.

Next, take the scion and cut a two-inch slice at an angle on two sides of the stem so that it meets at a point. You should be left with a two-inch “v” shape at the base of the cutting.

Insert this “v” into the cut you made in the rootstock and seal it tightly with grafting tape or compound.

After three or four months, remove the seal and ensure that the graft joint has healed. If it has, treat the plant as any other young quince tree. If not, reseal and check in another month.

Layering

If your quince sends up suckers or you’re allowing it to grow as a multi-stem shrub, you can propagate new plants via layering. This involves bending down one of the outer stems and partially burying it in the ground.

In the spring, look for a pliable, young branch, strip off all the leaves, and gently bend it down to the ground. Pin the end down with a heavy rock, wire, or whatever you have on hand. I like to use little tent stakes.

Heap some soil over the center of the stem and keep it evenly moist but not waterlogged.

When you see new growth emerging out of the area where you heaped soil, clip both sides of the plant off about six inches away from the new growth.

Gently dig up the quince plant, brush away the soil, and clip it even closer to the growing stem. Replant in a new area.

Transplanting

Planting a tree that you purchase is the easiest, though most expensive, way to get started growing quince.

Dig a hole the same depth and three times as wide as the growing container. Add some well-rotted manure or compost to the removed soil to create a loose, fertile mixture to nourish your young plants.

Remove the quince from its pot and gently loosen up the roots so they flare outwards rather than growing in a circle.

Place the plant in the hole, and backfill with the amended soil. The plant should be sitting at the same height as it was in the container.

How to Grow Quince Trees

Quince trees grow in Zones 5b to 9, as we mentioned. But USDA Hardiness Zone isn’t the only consideration.

The fruits are the most flavorful and juicy when grown in hot, dry climates with slightly acidic soil. You can grow quince in cooler, wetter regions, but the fruit probably won’t be as sweet and juicy. They’ll still cook up nicely, though.

In Zones 4b and parts of Zone 5, you can get away with growing the quince tree espalier against a south-facing cement or brick wall. Heap lots of mulch around the base of the plant to protect the roots during the winter.

If you have very alkaline soil, I recommend growing a different species as quince requires soil with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0.

You can amend your soil to make it more acidic, but you’ll be fighting a constant and potentially losing battle. If you decide to give growing a try anyway, your plants may be chlorotic and stunted if you don’t keep the soil neutral to slightly acidic.

The alternative is to grow a dwarf quince plant in a large container or a deep raised bed filled with loose, rich, well-draining soil.

Well-draining, organically-rich soil is best, but quince trees can tolerate some clay.

To grow the biggest fruits and an abundance of them, make sure your plant is in full sun, with more than eight hours of sunlight exposure each day. The fruits will be sweeter and more flavorful if they ripen in full sun than they would in shadier conditions.

Initially, keep the soil moist around young trees, you want it to feel like a well-wrung-out sponge at all times. After a year, you can basically let Mother Nature take over. Quince trees tolerate a good amount of drought, though they do better with regular moisture.

Generally, quince trees need about an inch of water per week. If rainfall in your area doesn’t take care of that, you’ll need to use supplemental irrigation.

Of course, if you have a soggy week you can skip the next or if you have an extremely hot and dry month, you might want to add a bit more to be safe.

Water deeply all at once, as opposed to adding a little bit each day.

Also, keep in mind that while a quince tree will survive through some drought, surviving is not the same as thriving.

Quince are self-fertile, but if you provide them with a friend nearby for pollination, they will flower and fruit more abundantly. They will also be pollinated by crabapples.

Once these plants are established, they’re pretty easy to care for and are relatively sturdy.

Growing Tips

- Provide quince trees with an inch of moisture a week.

- Plant in full sun for best fruit production.

- Grow in loose, rich, well-draining soil.

Pruning and Maintenance

Watch out for those suckers! Young trees, in particular, send out lots of suckers, and if you’re not careful you’ll end up with a big shrub rather than a tree.

Prune these out as you notice them, cutting right at the soil line.

Or you could just leave them to form a big thicket, there’s nothing wrong with a fruit-producing hedge in my opinion.

The flowers and subsequent fruits develop on new wood, so it’s important to encourage lots of new growth. The best way to do that is to trim the plant regularly. It’s not absolutely necessary for fruiting, but it will increase production.

If you’ve ever pruned a pear or apple, the process is the same. Read our guide to pear tree pruning for the full rundown.

Always remove any dead, diseased, or deformed branches as soon as you see them.

Fertilizing is a key part of growing a healthy quince plant. Fortunately, quince aren’t super demanding in that area.

You can apply an all-purpose food once in the late winter, following the manufacturer’s directions.

Down to Earth All-Purpose Food

Down to Earth’s All-Purpose Food is an excellent option and comes in pound-, five-pound, and 15-pound options at Arbico Organics.

Grab one of the larger containers because you need a pound of food per inch of trunk diameter.

Apply your fertilizer from the drip line to a few inches away from the trunk.

Fruiting Quince Cultivars to Select

There have been many breeders over the years working to try and create fruits that are more palatable straight off the tree, including noted horticulturist and botanist Luther Burbank in North America. A few of his cultivars are popular in cultivation today.

Quince trees need about 300 chill hours and all are self-fertile. That means they need 300 hours under 45°F and they don’t need a partner for fertilization.

Champion

‘Champion’ has white to pale pink blossoms followed by early ripening greenish-yellow, pear-shaped fruits.

It’s a reliable, heavy producer, which has made it one of the more popular options since it was first released to market in the 1870s.

‘Champion’

You can find it in both standard and dwarf sizes, and it does extremely well espalier.

Find one for your garden at Nature Hills Nursery.

Cooke’s Jumbo

Sometimes called ‘Golden,’ this quince produces the largest fruits of any cultivar. Grower Herbert Kaprielian of Reedley, CA, discovered this plant in Dinuba, CA in 1960.

The 12-foot tall shrub or tree grows pear-shaped fruits that are twice the size of the typical quince.

It also doesn’t need much in the way of chill hours to produce. Just about 100 hours should do it.

Pineapple

‘Pineapple’ was bred by Luther Burbank in 1899 and is the most popular cultivar in North America.

It has smooth skin on a pear-shaped fruit and firm, dry flesh. This isn’t the most fragrant option, so if you’re hoping to set out a bowl of fruit to fill your home with the unique scent, try another cultivar.

The fruit cooks up beautifully, and the tree is exceptionally productive, ready for harvest earlier than most other cultivars. It’s sweet enough to eat fresh if the fruit is allowed to ripen on the tree.

Van Deman

Another of breeder Luther Burbank’s beautiful creations, this cultivar ripens early with pear-shaped, extremely fragrant fruits.

If you want a classic option that has yet to be improved on, ‘Van Deman’ is your tree.

The tree produces tons and tons of fruits that are packed full of flavor.

It’s so delicious that it won the Wilder medal at the meeting of the American Pomological Society in Washington in 1891.

Managing Pests and Disease

Quince isn’t particularly troubled by pests. The real problem lies in a single disease that has caused growers to abandon these fruits in droves.

Let’s talk about minor irritants before we discuss that.

Herbivores

Are you struggling with deer in your apple or pear orchard? Plant quince! They smell so magnificent that they’re apparently irresistible to deer. The only other tree these ungulates like better is the “deer candy” persimmon.

If you’d prefer the ungulates don’t steal all those fruits you’ve been working so hard to grow, read our guide to learn how to deal with deer.

Less often, birds will peck holes in the ripe fruits, but the hard skin is a deterrent. You can avoid this pretty easily by picking them before the birds get to them.

Insects

There are many insects that will feed or live on quince trees, but unless your tree is already stressed or sick, they don’t usually cause much of a problem.

I say “usually” because there is one insect – the borer – that can be a serious problem.

Borer

Quince has its very own borer known as sad goat, apple-trunk, or quince borer (Coryphodema tristis). This species is only found in Africa, however.

In North America, it’s the flatheaded appletree borer (Chrysobothris femorata) that is out there wreaking havoc in quince orchards.

The adult is a metallic green-copper beetle that lays its eggs under the bark of trees in spring. The emerging larvae bore into the wood to overwinter and pupate.

As they bore into the quince tree, they cause damage that can weaken it.

Even worse is the roundheaded appletree borer (Saperda candida), which is a white beetle with three brown stripes. The adults lay eggs in summer under the bark and when the larvae emerge, they tunnel further into the tree to overwinter and pupate.

This damage causes weakening and creates large holes in the sapwood that can lead to tree death. Just a few borers can kill a quince tree.

Look for sap stains on the bark, which just look like dark streaks. If you cut into the area with the sap stain, you can often find the hole and the borer inside.

If you don’t see a worm, you can stick a flexible wire into the hole, and you’ll usually stab it. Do this each year, and you can generally keep the infestation under control.

Otherwise, you can apply a product that contains the beneficial bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis v. kurstaki (Btk). This bacteria kills the insects in their larval stage.

Start applying in the spring after the flowers fade and repeat every ten days throughout the summer.

Bonide Thuricide

Arbico Organics carries Bonide’s Thuricide, which contains Btk. Pick up a quart or gallon ready to use or an eight- or 16-ounce concentrate.

Codling Moth

Don’t even say the words “codling moth” (Cydia pomonella) when I’m in earshot.

They trouble my apple trees every year, and while they seem to be less interested in quince, they will still visit.

Codling moths aren’t super common in commercial orchards because they use lots of pesticides to keep the pests at bay. But organically-grown quince trees and home orchards are susceptible.

The adults are gray and brown, measuring about half an inch long. The three-quarter-inch larvae are creamy white or pale pink with a black head capsule.

The adults are no big deal, but those larvae suck. They tunnel into the fruit to eat the seeds, then turn around and head out to pupate.

The tunnel they leave behind rots the flesh and mars the appearance of the fruit.

A lot of people won’t eat a quince after it has been munched on by codling moths, and you certainly can’t sell them. They won’t store well, and they’re likely to rot quickly. You might be able to slice out the parts of the fruit that are still good, but it’s hardly ideal.

There can be two generations per year, and you can assume in most areas that they will be present every single year.

Pheromone traps confuse the adults and stop them from breeding. Those that do breed can be controlled by spraying the tree with horticultural oil.

Most locations in the US will have an extension office that will let you know when the timing is right to spray each year, based on temperature and tracking.

Bonide Horticultural Oil

You can pick up some horticultural oil at Arbico Organics in a variety of package sizes.

Btk, Trichogramma wasps, and beneficial nematodes can also be useful, though not quite as effective.

You can also spray with pyrethrin starting after the flowers drop and continuing every eight weeks until you harvest.

This is my least favorite option because it kills beneficial insects as well as the bad guys.

That has a snowball effect in the garden. Your aphid-infested roses could very well be caused by treating a quince tree with pyrethrin.

You can also opt to use the time-consuming but highly effective method of tying mesh bags around the fruit when the buds develop. You might not be able to cover the whole tree, but you can usually protect enough to have a massive harvest.

Scale

Both soft and armored scale will take the opportunity to feed on quince trees, though they rarely do much damage unless there are very large numbers or they are feeding on a young, weak tree.

You can usually spot them by flipping over a leaf and looking for flat, oval bumps that can be scraped off using your fingernail.

Beneficial insects typically keep these pests under control, so limit the use of insecticides in your garden and plant lots of species to attract pollinators, particularly native flowering plants.

Learn more about how to manage scale in our guide.

Tent Caterpillars

I’m listing these insects because although they don’t do much damage to the tree, they tend to horrify gardeners with their masses of webs filled with wiggly worms.

I get it. The first time I saw an infested tree, my entire body became one giant goosebump. They look like something out of a horror film.

In reality, even if they eat a large amount of the foliage one year, they rarely return in the same numbers in following years, so trees recover just fine.

If they bug you (ha!), use a broom to sweep them out of the tree onto a tarp and then dispose of them. For the love of Pete, don’t try to burn them out of the tree! It damages the plant and it could end badly for you and your local fire department.

Learn all about tent caterpillars and controlling (or tolerating) them in our guide.

Disease

Now we’ve come to the bad news. Fireblight is a prevalent and devastating disease that affects quince.

Many of the new cultivars are resistant (not immune), and I highly recommend you choose one of these if trees in your orchard have suffered from fireblight in the past.

Fireblight

Fireblight is a common problem in fruit trees and one of the reasons that quince fell out of favor.

It’s caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora and thrives in humid areas in temperatures from 65 to 75°F and attacks all species in the Rosaceae family.

Once infected, the leaves first wilt and then turn brown and crispy. The whole branch curves downwards, taking on a C shape.

When the bark is infected, it forms cankers, peels back, and dies. And fruit production? Forget about it. Your harvest will be greatly reduced – if the tree manages to grow any healthy fruits at all.

Excess nitrogen in the soil promotes this disease, so make sure you test your soil before applying fertilizers.

Bad pruning or a lack of pruning and broken branches leave the plant open to infection. Remove suckers as these tend to be the first to become infected. If you water, do so at the base of the plant at the soil rather than on the leaves or wood.

If your plant is infected, pruning out the symptomatic areas or removing young infected trees is about your only option. Otherwise, it’s highly likely that the disease will eventually kill your tree.

Leaf Spot

Fungal leaf spot caused by Fabraea maculata (syn. Entomosporium mespili) isn’t just an aesthetic problem, as the fruits might be disfigured, as well.

I’m sure you guessed that the pathogen causes spots on the quince tree’s foliage. These are dark brown or black, sometimes with tan or yellow centers and dark red or purple halos. These spots enlarge and merge as they mature.

The fungi can inhabit live or dead tissue and the spores are spread by water.

That means managing the problem involves removing symptomatic leaves, whether those are on the tree or fallen on the ground, and watering at the soil level.

You should also prune trees to open up the canopy and encourage airflow.

Copper fungicide applied in the spring can also suppress or kill the fungi. In addition to my hori hori knife, pruners, and a good spade, copper is one of the most valuable tools in my gardening shed.

It tackles many different fungal issues.

Bonide Copper Fungicide

Purchase it in 32-ounce ready-to-use, 16- or 32-ounce hose end, or 16-ounce concentrate at Arbico Organics.

Powdery Mildew

You’ve probably dealt with powdery mildew on your melons or pumpkins, but it’s also a problem on many other species and quince is one of them. In fact, the thin leaves of the plant seem to be particularly susceptible.

The symptoms include curled leaves coated in a white, powdery substance. This is the Erysiphales fungal spores. Fortunately, the disease is mostly an eyesore and doesn’t usually impact fruit production unless it’s severe.

Because it’s such a common problem, gardeners have figured out lots of ways to treat it, from applications of milk to heavy-duty fungicides. Learn more about how to manage powdery mildew in our guide.

Harvesting

Fruits typically ripen between September and November, depending on which cultivar you’re growing and where you live.

Do not pick the fruits early and try to ripen them after harvest as they will never be as sweet and flavorful as they will if they are allowed to ripen on the tree.

The only caveat is that you need to harvest the fruit before first frost or before the birds discover them.

Part of the reason store-bought quince never smells or tastes quite as good as homegrown fruits is because they’re usually picked while they’re still a bit green.

They never get the chance to achieve full ripeness, and are often described as “fuzzy,” but that’s only true of immature fruit. Once they age, they drop that fuzz.

To harvest the ripe quince, gently pull them from the tree. The fruit should come away without too much pressure. If you really have to tug, chances are they aren’t ripe.

Preserving

If you intend to make jelly or jam, leave the skin on and the core in place, as this is where a lot of the pectin is concentrated. However, it takes a lot of cooking to break down the skin and core, so feel free to carefully peel the skin and remove the core.

To make preserves, chop the fruit into small chunks and place them in a saucepan, and cover with water so the pieces are only just submerged.

Simmer until the flesh is bright salmon or red in color and turns soft if you press it with a fork. This process takes a while.

If you’re just cooking flesh, expect it to take at least 45 minutes, and even longer if you’re processing the skin and core as well.

Add sugar and your preferred spices to taste. Cardamom, allspice, star anise, cinnamon, clove, ginger, and nutmeg all work well with the flavor of quince. Cook a bit longer until it all breaks down and combines. Let it simmer until it reaches the consistency you desire.

You can also process the fruit into a paste, jelly, syrup, or jam.

The fruit can be frozen after skinning, coring, and cutting it up into chunks. Set the chunks on a baking tray in the freezer until frozen, then transfer to a plastic container or zip-top bag.

As much as I love quince, I have to admit that I hate peeling them.

The skin is rock hard and my fingers have barely escaped intact numerous times when trying to peel it off. Use caution when working with a sharp knife. Lots of people opt to use a vegetable peeler to be on the safer side.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Try mixing quince with apples or pears to add some color and flavor to your jams and jellies.

I’ve never made it myself, but I’ve had a friend’s candied quince, and it was a bite of heaven. In addition to compote, jam, jellies, tarts, cookies, cakes, and other sugar-filled options, you can also use the fruits in savory recipes.

The poached flesh is a marvel served with fish or pork. In Armenia, the cooked fruit is served with lamb.

Have you ever seen membrillo paste (dulce de membrillo) at the grocery store? You’ll see it in the deli or cheese section. It’s a paste made with quince, and is heavenly in a charcuterie.

Quince somehow manages to play well with stronger flavors like blue cheese and olives, as well as the milder fare like brie.

Visit our sister site, Foodal, to learn how to set up the perfect meat and cheese board.

The flavor works well with mushrooms, balsamic vinegar, as a glaze on turkey, duck, or chicken, smeared with pate, mixed into sausage, in salads or empanadas. Who said these fruits weren’t useful?

Quince is also a classic choice for making cider.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous fruit tree | Maintenance: | Low |

| Native to: | Caucasus Region | Soil Type: | Loose, organically-rich |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5b-9b | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Summer, fall | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Attracts: | Pollinators, deer |

| Spacing: | 10 feet | Companion Planting: | Alliums, borage, clover, dill, lemon balm, mint, yarrow |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as growing container | Avoid Planting With: | Lambsquarter, succulents |

| Height: | Up to 25 feet | Uses: | Edible fruits |

| Spread: | Up to 20 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Tolerance: | Drought | Subfamily: | Amygdaloideae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Cydonia |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Deer, birds; borers, codling moth, scale, tent caterpillars; fireblight, leaf spot, powdery mildew | Species: | Oblonga |

Join the Bacchanalia

In Turkey, where most commercial quince are grown, “to eat the quince” is slang for getting into trouble. In this case, growing quince is the best kind of trouble.

The fruit smells and tastes so decadent that you can easily imagine it featuring front and center in a modern bacchanalia.

Unjustly forgotten in North America, the trees are once again receiving the attention they always deserved. Truly, once you smell the mature fruits and sink your teeth into the cooked flesh, you’ll be willing to go to any lengths to bring one of these trees into your garden space.

With the exception of fireblight, these trees really aren’t that big of a challenge to grow. I’m not sure how they earned the reputation as fussy when they take less work than apples and pears.

The most difficult part of growing these apple relatives is dealing with the tough skin. It’s no joke!

Alright, now that we’ve covered all the details, we can dive into the good stuff. How are you going to use yours? I need more recipes! Share yours in the comments section below.

Unless you only have a spot for one fruit tree, you’re probably going to want to expand your options at some point. If so, check out these guides to growing fruit trees for more inspiration: