A Golden Age of Renewables Is Beginning, and California Is Leading the Way

California has hit record-breaking milestones in renewable electricity generation, showing that wind, water and solar are ready to cover our electricity needs

LADWPs Pine Tree Wind Farm and Solar Power Plant in the Tehachapi Mountains of California.

Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

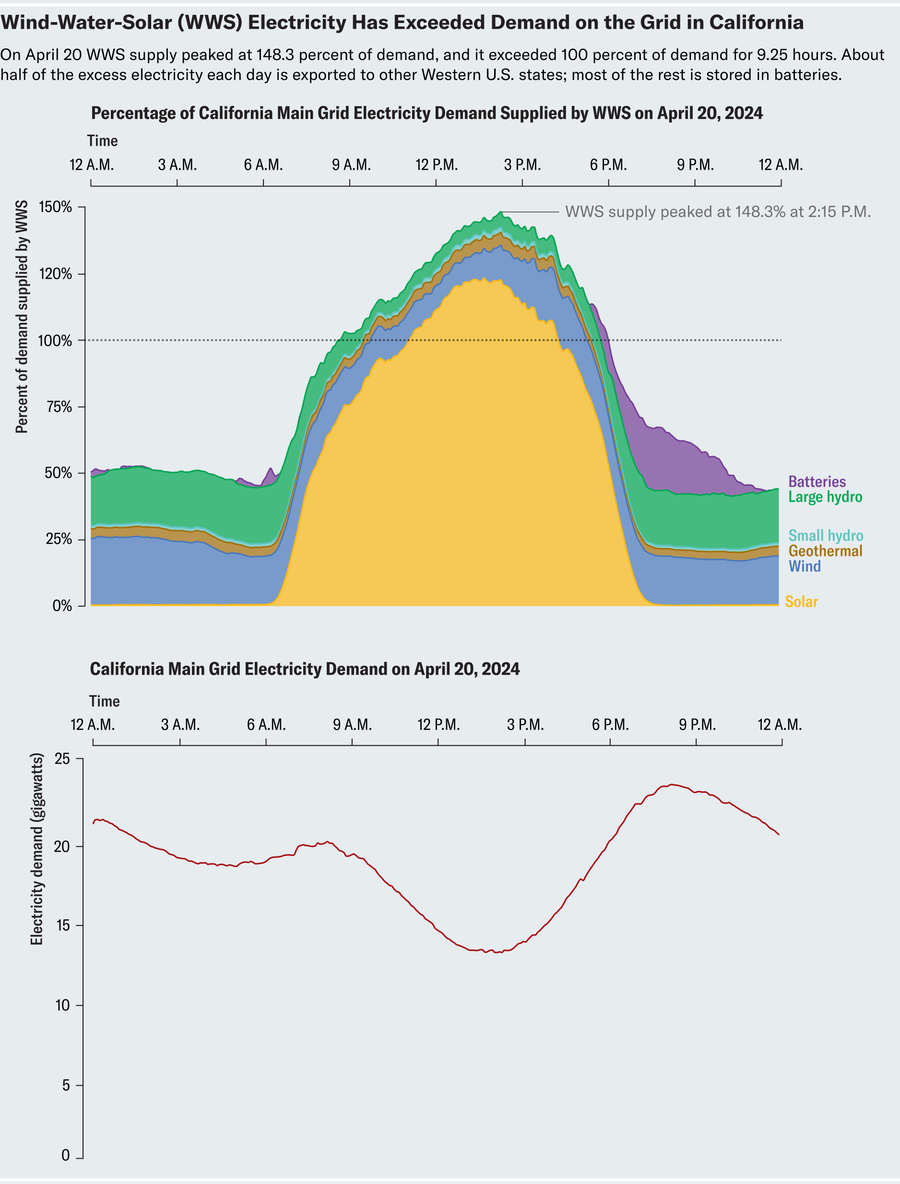

Something spectacular is happening in the Golden State. California—the fifth-largest economy in the world—has experienced a record-breaking string of days in which the combined generation of wind, geothermal, hydroelectric and solar electricity has exceeded demand on the main electricity grid for anywhere from 15 minutes to 9.25 hours per day. These clean, renewable electricity sources are collectively known as wind-water-solar (WWS) sources.

It is impossible to understate how monumental this clean, renewable energy milestone is and how quickly WWS supplies have ramped up. In 2022 and 2023, California reached 100 percent WWS on the grid but only for the occasional day on a weekend—never two days in a row and never during the week. Now it’s an almost daily occurrence during spring. And it heralds in a new era of clean, renewable electricity, which will ultimately power the entire U.S. and the rest of the world for nearly all energy purposes.

At press time, for 39 of the past 47 days (through April 23, supplies of WWS electricity have exceeded demand on the grid. On April 20, WWS supply peaked at 148.3 percent of demand (see top chart below). About half of the excess electricity each day is exported to other Western U.S. states; most of the rest is stored in batteries. Some electricity is even thrown away due to lack of demand. Battery electricity is then used to provide electricity for California’s grid at night. On April 21, nighttime battery electricity output reached a new record of nearly 6.5 gigawatts on California’s grid. That is the equivalent of the output of more than seven nuclear reactors and one quarter of the maximum grid demand during all seasons except summer, when demand can double at night.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Moreover, on April 11, solar alone provided more than 100 percent of demand for the first time ever in California: solar supply exceeded demand for 1.5 hours, reaching a peak of 102.4 percent of demand during that period. That record was subsequently smashed on April 21, when solar peaked at 123.9 percent of demand.

That solar output does not even include most of California’s rooftop solar output, which supplied about 12 percent of electricity generation in the state last year. Rooftop solar directly powers homes and businesses, so while it does not contribute much directly to overall grid supply, it does reduce demand significantly during the day, as seen in the bottom graph above.

The string of days that have reached 100 percent WWS has so far occurred only during the end of winter and much of spring, when temperatures have been mild and solar output has been high. Electricity demand during summer can double because of heavy air conditioner use. Whether there will be days that reach 100 percent WWS during summer this year is yet to be seen. With the future growth of both utility-scale and rooftop solar, however, California will ultimately provide 100 percent WWS during summer daytime hours as well. Solar, though, provides electricity during the day only. Nighttime demand can be met by a combination of using batteries powered by daytime solar, offshore wind, shifting more hydropower production to night hours, and setting electricity prices so that demand shifts to daytime.

Detractors claim that the growth of renewables in California has resulted in high electricity prices. California has the third-highest electricity prices in the U.S. To the contrary, the growth of WWS in California has prevented prices from rising further. This effect is demonstrated by high WWS generation but low electricity prices in other states: Of the 11 that have higher annual-average production of WWS as a percent of demand than California, 10 are among the 25 states with the lowest electricity prices. Five are among the 10 states with the lowest prices.

So why are California’s electricity prices high? California has the third-highest natural gas prices in the U.S. and still uses that fossil fuel for backup electricity. In addition, utilities have passed on to customers the costs of the San Bruno and Aliso Canyon gas disasters, gas pipe retrofits, wildfires caused by transmission line sparks, and burial of transmission lines to reduce such fires.

California still has a long way to go to become 100 percent WWS-supplied every hour of every day of every year in its electric power sector and an even longer way to go to transition transportation, buildings and industry to WWS. But as my colleagues and I have found in our 100 percent all-sector energy plans for California and the other 49 states, it is possible to transition with enormous financial benefit to consumers. Similarly, our energy plans for the world indicate the potential to convert all countries to WWS at low cost. California’s success and all of these plans indicate that fossil fuels with or without carbon capture, bioenergy and nuclear power are not needed to power future grids. The amazing progress seen so far in California in 2024, even compared with just last year, is a reason to believe the future will be golden in the Golden State.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.