When Lene was a child, she took comfort in a strange nighttime routine. While lying in bed just before she fell asleep, her bedroom would begin to warp, and her body would do so along with it. The far wall would stretch away from her head, her legs lengthening to meet it until she felt like she could touch the door with her toe if she tried. And all the while, it seemed as if she was floating in the corner, observing her distorted body.

“The first time I was very scared,” Lene says, recalling she was between seven and nine years old at the time. “I didn’t tell anyone, because if I told my mom, she would just say, ‘Eh, it’s nothing.’” She recalls that the episodes began happening every night, and eventually they became somewhat comforting. By adolescence, they had stopped, and she largely forgot about them.

Then, a few years ago, Lene, now age 59, learned that her experience had a name. She was at a hospital in Denmark where she works as a secretary in the neurology department. During a meeting where she was taking notes, a neurologist mentioned a patient with something called Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Intrigued, Lene did some research on Google, where she immediately recognized her own experience.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

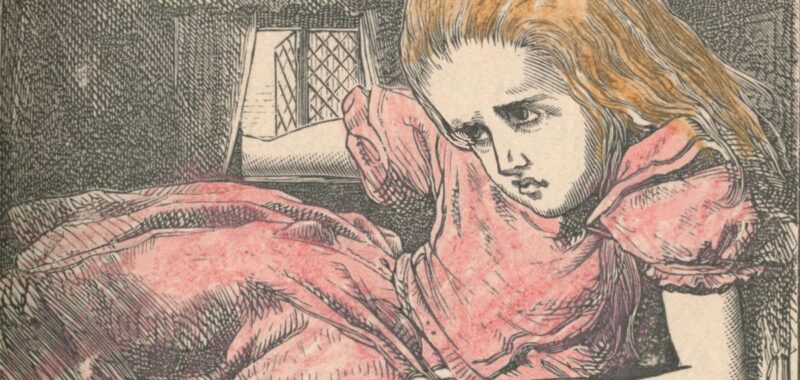

“All my life, since I was a child, I had this thing I couldn’t explain. And suddenly there was a word for it,” Lene says. During episodes of Alice in Wonderland syndrome, the world appears distorted, in many of the same ways that are described in Lewis Carroll’s famous novel, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Bodies can morph out of shape; time can speed up or slow down; colors can fade or intensify. Often, these symptoms come with a sense of unreality called depersonalization or derealization. These distortions usually last between minutes and days and are known to be triggered by migraine, epilepsy, brain injury, drugs and infections.

While it’s rare to be diagnosed with the condition—fewer than 200 clinical cases have been officially reported since 1955, mainly in children, and it doesn’t appear in any mainstream diagnostic handbooks—Alice-like symptoms appear to be relatively common. One survey study published in 1999 found that some 30 percent of participants had experienced at least one kind of visual distortion in their life. And around 16 percent of migraine patients in a recent study also reported symptoms of Alice in Wonderland syndrome throughout their life. Some researchers have theorized that Carroll experienced these symptoms himself because he was known to experience migraines.

“The symptoms are as fantastical as the narrative of the book,” says Alberto Paniz-Mondolfi, an infectious disease physician at Mount Sinai in New York City, who has encountered the condition throughout his career. “When you don’t have answers, that is an enigma. And this is a condition that remains, in all of its aspects, largely unanswered.”

Still, researchers have begun to assemble many of the pieces of the Alice in Wonderland syndrome puzzle. The number of published studies on the condition has more than doubled since 2010, giving researchers important new insights into what causes these symptoms, says Jan Dirk Blom, a psychiatrist at Leiden University in the Netherlands and author of a 2020 book on the syndrome. And most recently, researchers have uncovered a potential answer to one of the syndrome’s biggest mysteries: What happens in the brain when people enter the rabbit hole?

The Looking Glass

We often think that our five senses allow us to observe the world as it truly exists—that “our brain is some sort of canvas or display for the reality” around us, says Maximilian Friedrich, a neurologist at University Hospital of Würzburg in Germany. “But it turns out that this is not the case. Perception is an active process.” The brain does not record reality through sensory input like a camera; it synthesizes, interprets and reconstructs it.

This reconstruction process can go wrong in many ways, leading to the distortions common in Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Neurologists have given these distortions names: Micropsia and macropsia mean objects appear smaller or larger, respectively, than they really are. Prosopometamorphopsia happens when faces seem to twist out of shape. With dysmorphopsia, straight lines appear wavy, and with kinetopsia, stationary things appear to be in motion.

Nonvisual symptoms are common, too. People might have an illusory feeling of levitating in the air or being outside of their body, or they feel like parts of their body are becoming larger, smaller or otherwise distorted. Some people report the unnerving sensation that their body is splitting in two. These symptoms can be very frightening—or simply inspire curiosity because, generally, people with Alice in Wonderland syndrome are aware that what they are feeling or seeing isn’t truly happening.

In 1955 psychiatrist John Todd suggested the name “the syndrome of Alice in Wonderland” to refer to a handful of cases involving these perceptual disturbances. In most of those cases, the person suffered from migraines or epilepsy—or both. In fact, Todd cited Lewis’s own history of migraines as part of the reason for the name, which captures the whimsical, eerie feeling that can be evoked by both the novel and the syndrome’s distortions.

Alice in Wonderland symptoms themselves are generally benign, Friedrich says. Individual episodes typically stop on their own, but they can recur across someone’s life, especially if they’re triggered by migraine or epilepsy. In the case of a brain injury resulting from events such as strokes, the episodes may cease on their own as the brain recovers, Friedrich says.

Even with benign symptoms, the syndrome can have profound effects on a person’s life by shaking their perception of reality. “Perhaps that is the most frightening aspect of Alice in Wonderland syndrome: that it can make us doubt the most simple, fundamental things about reality,” Blom wrote in his book on the syndrome. In it, he told the story of a woman he once treated who had episodes of Alice in Wonderland syndrome several times a week since childhood, often in conjunction with epileptic seizures and migraines. The middle-aged woman, who he called Ms. Rembrandt, would have “spells” where she would see her body as a “tiny, worm-like object dangling under a hugely bloated head.” These disturbances took a massive toll on her mental health and the course of her life. Fortunately, after Blom examined her, he prescribed an antiepileptic medication that stopped the spells, allowing her to feel like she was living an ordinary life for the first time.

The Alice Network

If you asked 10 people with Alice in Wonderland syndrome about their experiences, you would likely hear 10 very different stories, hinting at different constellations of symptoms and causes. With more than 60 possible symptoms, is it correct to think of this as one syndrome at all?

“One would be excused to suppose that there is little connection between these symptoms,” Blom says. In fact, until recently, researchers hadn’t been able to pinpoint what parts of the brain were involved in these disturbances. When Friedrich compiled brain scan and autopsy data from 37 people who had experienced Alice in Wonderland syndrome after a brain injury—the second most common cause of the syndrome in adults—they found damage, such as lesions, in different regions across the brain, with no clear commonalities.

“At first, we were scratching our heads, saying, ‘This doesn’t make sense at all,’” Friedrich says. “Where’s the unifying factor here?”

But a lesion that occurs in one area of the brain can also affect another. That’s because the brain is made of complex, interlocking networks, and in the past decade, researchers have finally gained the tools to map them out.

“You damage a spot in the brain, it’s going to have an effect on everything that spot in the brain is connected to,” says Michael Fox, a neurologist at Harvard University. Using a technique called lesion network mapping, Friedrich, Fox and their colleagues were able to investigate those connections.

“It was a eureka moment for me” when the results came in, Friedrich says. The researchers’ analysis revealed that two brain regions were highly connected with the diverse Alice in Wonderland lesions: the right extrastriate body area, a region of the visual processing system toward the back of the brain that helps to govern our perception of bodies, and the inferior parietal cortex, which is involved in perceptions of size and magnitude.

“It all made sense,” Friedrich says. “If the size processor and the body processor are both out of balance, then it’s an intriguing hypothesis, at least, that this could explain the changes of body size in Alice in Wonderland syndrome.”

Blom agrees. “Even though superficially [the syndrome] may seem to be a mixed bag of individual symptoms, it is now clear the brain areas involved … form a network of interconnected structures,” he says.

But what about migraine, the most common cause of Alice in Wonderland syndrome in adults? The researchers identified five instances from previous research where people with migraines had an Alice in Wonderland episode while in a brain scanner. The abnormalities in these scans had a “highly significant overlap” with the Alice in Wonderland network identified from the brain injury study, Friedrich explains. This overlap between the syndrome and migraine could explain why they often occur together.

“There’s no such thing as an Alice in Wonderland spot,” Fox says. “It’s an Alice in Wonderland circuit.” And both migraine and stroke, under the right circumstances, may be capable of impacting regions in this circuit enough to trigger those wonky perceptual symptoms, he adds.

Infectious diseases, too, seem to be able to cause these disturbances. Bacteria, viruses, protozoa and prions have all been documented to trigger Alice-like symptoms in infected humans. During the COVID pandemic, doctors around the world began reporting cases of children who developed Alice in Wonderland syndrome after infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. Influenza, Epstein-Barr virus and varicella-zoster virus (which causes chicken pox) are known to be linked to the syndrome, too. Paniz-Mondolfi’s first encounter with the condition was during an outbreak of Zika virus in Venezuela in 2016. He treated a 15-year-old girl who had recovered from the virus but was experiencing perceptual disturbances. She was brought in by her mother, who feared the girl was possessed.

“Having experienced the symptoms myself, I know how freaky this can be,” Paniz-Mondolfi says. On one occasion, he experienced a bizarre distortion of shapes and the sensation of his body splitting in two after accidentally smoking a cigarette laced with yopo, a plant with hallucinogenic properties, while serving as a rural physician in Venezuela.

Pathogens such as Zika and SARS-CoV-2 could be acting directly on particular regions of the brain to cause these symptoms, Paniz-Mondolfi says. But he thinks the body’s inflammatory immune response is a more likely culprit. Perceptual distortions such as those of Alice in Wonderland syndrome are common in fever, for example. (Blom experienced a similar disturbance when ill with food poisoning once.) And in cases where the infection has already resolved, a long-lasting immune response to the virus could somehow affect the brain and cause these symptoms, similar to the proposed mechanism for long COVID.

Curiouser and Curiouser

Then there’s another lingering mystery: Why does Alice in Wonderland syndrome seem to be more common in children? Paniz-Mondolfi theorizes the answer may lie in a child’s tendency to mount more robust immune responses than an adult. A 2016 review of clinical cases found that encephalitis, often caused by infection with Epstein-Barr virus, was the most common cause of the syndrome in children.

In many childhood cases, it’s not clear what may have caused the syndrome at all. Carmen Vidal Fueyo, a user experience designer based in Brussels, experienced episodes of Alice in Wonderland syndrome from the age of six until puberty. Her episodes would always begin with a sudden sense of impending doom, followed shortly by the feeling that her hands were inflating in size. Objects around the room appeared to grow large enough to suffocate her or so small as to disappear entirely. She recalls that the episodes happened every few months until she hit puberty and began experiencing migraines and vertigo.

One day as a teenager, she came across a post on X (then called Twitter) that described Alice in Wonderland syndrome. “I cannot even explain the feeling,” she says. “For so long, that was a mystery of my life. I didn’t know if one day I was going to find out that I had a brain tumor.” She has since revitalized a subreddit dedicated to the syndrome as a place for people to share their experiences free of judgment.

For Vidal Fueyo, Alice in Wonderland syndrome wasn’t a whimsical presence in her life, as the name can imply. “It was not a good experience,” she says. The episodes were terrifying and usually came at night. “For the longest time I was afraid to go to my friends’ houses” for sleepovers, she says. She tried communicating what was happening to her mother but struggled to explain it.

Vidal Fueyo shares Paniz-Mondolfi’s and Friedrich’s suspicions that the syndrome is more common than reported, especially in children, who may not have the language to communicate these experiences to adults.

“Maybe it’s really normal,” Friedrich says—just a part of the neurodevelopmental process in which the brain is “tuning its perceptual mechanisms” to perceive the world accurately. “It could be that we all can get these little perceptual glitches when we’re young.” Friedrich himself, who suffers from migraines, thinks he can recall one episode from his own childhood.

Lene hasn’t experienced Alice-like symptoms in decades. Yet the condition is still a part of her life. Lene’s daughter, after hearing about her mother’s experience, revealed that she had similar episodes when she was a child; they frightened her frequently until they ceased around adolescence. And now her five-year-old son—Lene’s grandson—has begun to experience these symptoms, too. It happens when he’s tired, often when the family is driving in the car.

“He is panicked, saying, ‘My feet are big, oh, my feet are so big,’” Lene says. “He can’t understand it. We don’t know how to tell him. How do we explain it to him?”

Lene reached out to Friedrich this year to explain her family’s situation after finding one of his papers. Friedrich wonders if genetics play a role in why all three people have had similar experiences. “There’s something to be investigated here,” he says.

Lene looks forward to what the researchers might find. “I would like to have some answers and a very good way to explain it,” she says, “especially for my grandson.”